Suke Wolton looks at how home ownership, thought to be the key to a voter’s heart, has created a nation addicted to credit and rising house prices.

Ever since the nineteenth century, people have argued that home ownership is political. This is generally understood to mean that home ownership affects people’s political attitudes, and is usually presumed to forge a conservative outlook. And so, it was thought that by increasing home ownership, Britain would become a more conservative country with more people having a stake in the existing social order. For conservatives, particularly, property was understood as the ‘historical basis of liberty and status’, and to provide the ‘philosophical basis for personal independence’.[1] After more than a century of government talk of the need to build more houses, has home ownership in fact proved to be the way to a voter’s heart for conservatism?

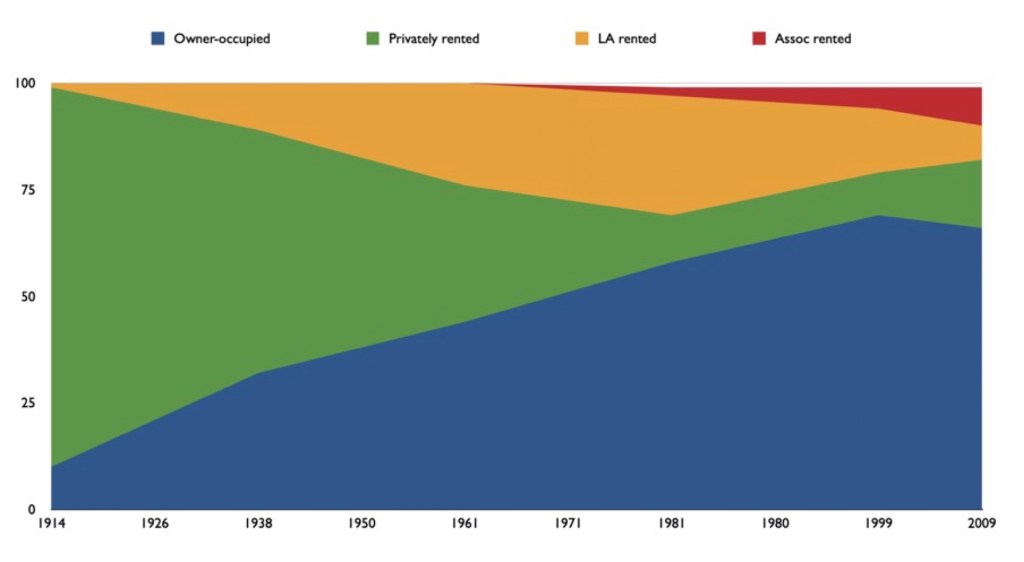

Home ownership grew through the twentieth century, peaking at about 69% of tenures in the early 1990s, and dropping back to around 64% since the millennium. [2] Before the First World War, private ownership was barely 10%, and following the war, Lloyd George claimed that the 1919 Addison Housing Act would provide ‘Homes for Heroes’ that would ‘keep the Bolsheviks at bay’.[3]

Actually, despite the ‘Marxist’ appearance of this materialist argument, back in the nineteenth century Frederick Engels had already contradicted this point when it was made by the anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, arguing that home ownership could not make workers into capitalists.[4] Notwithstanding Engels doubts, by the 1930s, it was widely assumed that a ‘property owning democracy’ would be a barrier to the growth of radical ideas.

The poor quality of existing housing for a large section of society strengthened this case for change and encouraged the growth of local authority-owned housing. Slum clearance increased significantly in the 1930s: many fine Georgian terraces that had become red-light districts were demolished, but also many new estates that we now revere were constructed.

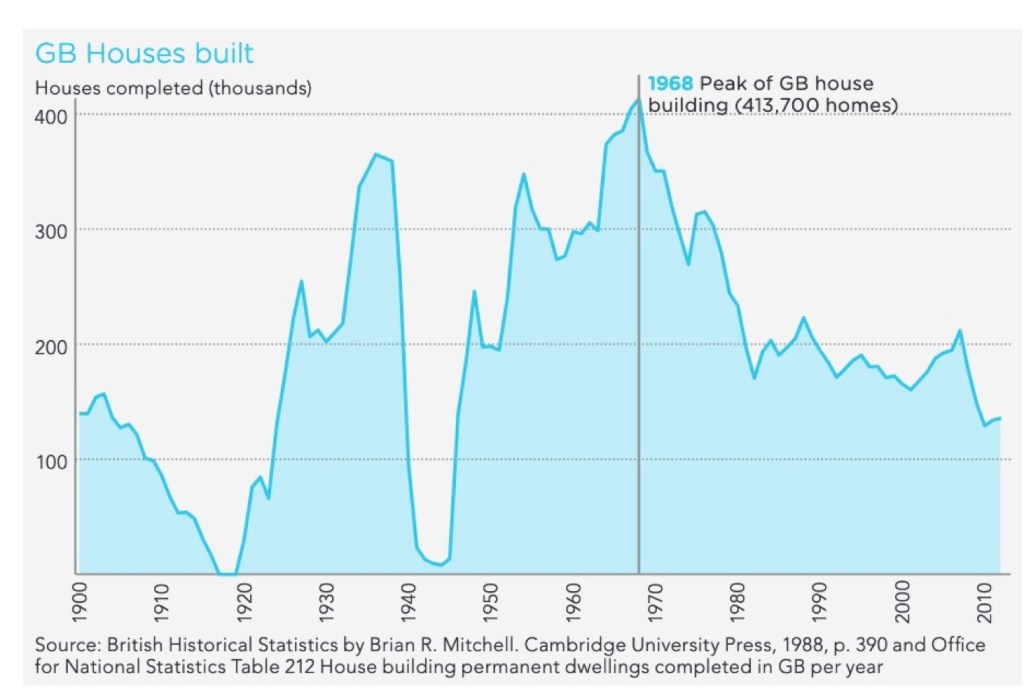

By the end of the Second World War, with the idea that British workers had fought for a ‘People’s Peace’[6], the provision of social housing was seen to be a priority. Now we look back at this high point of construction as a beacon to our miserabilist times, but at the time, it was recognised that even those levels of house building were not enough[7], especially as by 1950, it was clear that numbers were already declining[8]. The post-war estimate of the shortfall of houses lost to lack of building during the war, to bombing and to the growth in the number of households meant that it was estimated that the UK needed 10 million new homes.[9] One of the reasons that Labour lost the 1951 election is that they were unable to deliver more house construction. Indeed, Harold Macmillan contributed to his popularity, stating that: ‘Housing is a not a question of Conservatism or socialism, it is a question of humanity.’ [10] Despite the bipartisan agreement on the need to build, it continued to be a struggle:

And the peak in 1968, should also be compared to the house building of the 1930s (more on this later), which was almost as high.

That peak of house-building in the UK occurred under Labour in 1968. The Conservatives claimed that they had stimulated private house building while Labour claimed it was public authority building that made the difference. Certainly, the new growth of local authority high-rise buildings made it possible to create a lot of homes very cheaply.

Whether their tenants appreciated them is in more doubt. And while it is the case that through the 1950s and the 1960s both the private sector and the local authorities built, it is worth noting that standards were not great and the introduction of the National Building Regulations in 1965 were an attempt to appear to improve them without too great an impact on the construction industry.[12]

Post-war local authority housing, however, had turned out to be a mixed blessing. Lower rents and accountable landlords were a great boost to working-class families after the pre-war experience. However, corrupt councillors giving building contracts to their friends, the lowering standards of building regulations, poor construction methods and an infatuation with new untested building materials combined to make for pretty poor housing, not just in the immediate post-war rush, but especially in the 1960s and 1970s because of mass construction in tower blocks.[13] Social housing of the 1930s now looks almost grand compared to the quality of social housing since the 1950s.

As a result, local authority landlords and poor social housing were rapidly becoming an easy political target for the Conservatives. The Conservatives had tried (in Birmingham especially in the late 1960s[14]) to sell off council properties with a small success, but Peter Walker MP (and former Environment Minister) argued in the October 1975 issue of the Municipal Journal that it would be cheaper to give away council houses. He calculated that the cost of supervision, management, maintenance and repairs was £427 million per year, while the housing stock was only worth £172 million at that time and the government would save money by donating the property to their tenants[15]. In the end, despite the Conservatives strong desire to save money, it was felt that the council properties should be sold at a discount so as to make sure the properties retained their apparent value. The final arrangement (finalised in May 1976) for the ‘Right to Buy’ (RTB) scheme was to discount the houses to one third of their market price after three years of tenancy, with a one per cent increase in discount per year of tenancy up to a maximum of 50 per cent[16]. The ‘Right to Buy’ legislation was then implemented in 1980, having been a key manifesto commitment for Margaret Thatcher’s government. The manifesto promise of RTB was popular, gaining 73% support (with only 12% opposed) in 1979.[17]

The Conservatives had assumed that privatisation of home ownership was a way of challenging Labour loyalties and would be intrinsically popular[18]. And indeed, as a step away from the post-war housing developments that were so often unfriendly to their tenants, it was an easy political goal. But while the Conservatives imagined that property-owning would encourage voting Conservative, it was not necessarily the up-and-coming and skilled of the working class, the targeted former Labour voters, who were persuaded to exchange rent for a mortgage.

Detailed studies of the people who decided to buy their council properties found that the decision to buy was often a reaction to the new council policy of selling council houses to private landlords; or changes in rents; and, interestingly, often it was after a period of unemployment where the council tenant had used this time to improve their own dwelling and wished to stabilize their tenure. Far from deciding to ‘enter the property market’ or even consider purchasing in order to sell at a higher price later, it was thought to be a way to make safe their investment having fixed the kitchen or improved the bathroom[19]. Although Right to Buy was introduced in 1980, after a first flurry of sales, it did not remain popular in those early years. It was largely after 1987, when employment started to rise again, and following the initial boom in DIY shops (and activity) that RTB took off[20]. Moreover, the changes that had taken place earlier in the post-war period of rising suburbanization, with inner-city dwellers moving to the edge of conurbations, had also had the effect of dissipating and disaggregating working-class communities, not just the RTB policy.[21]

The other side of the RTB legislation was an attack on local authorities as the legislation restricted local authorities to spend no more than 25% of the (already discounted) purchase price on further house building.[22] As a consequence, local authority spending on construction plummeted. The graphs above and below demonstrate the drop in building by local authorities very clearly.

The construction slowdown was accentuated by two causes. First, local authorities were not allowed capital expenditures if they were indebted (and the sales of council houses, being discounted, did not raise much money). And second, the houses they did build were liable to be bought from them at low rates a few years later. Local authority investment in housing declined from £12bn in the mid-1970s to £2bn in the late 1990s.[23] And the discounts for council tenants were significant (as the Conservative government felt the properties were expensive to maintain), initially between 33% and 70% of market price depending on the length of the tenancy (and type of home). Between 1980 and 1999, 2.2 million (30% of tenants) had exercised their right to buy.[24] The government, as it sold off the post-war housing assets, however, made £4bn in the first three years, which was not used to build more houses.[25]

As property values rose in the late 1980s, so it appeared that the property market could be a place to make money (see graph below). And indeed, many people sold on their council properties after the designated period (usually three years).[26]

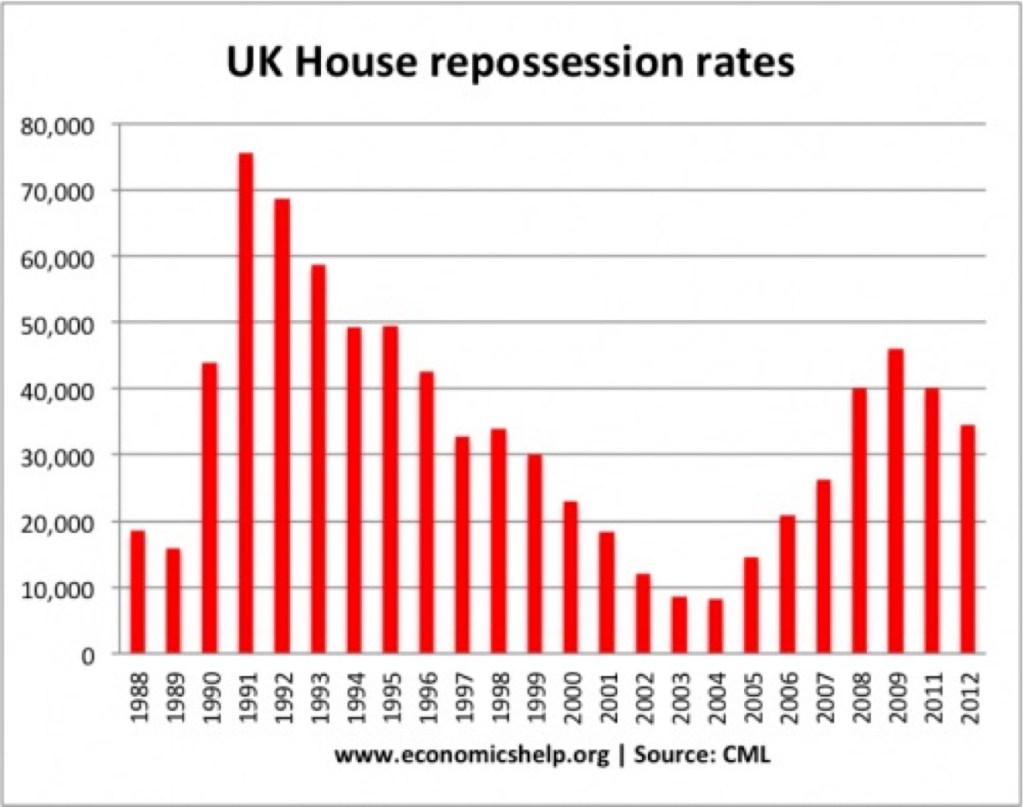

The number of council tenants turned into home-owners that were able to benefit was fairly small, particularly as the early 1990s saw another slow-down, and people, especially in the north of Britain, were caught in ‘negative-equity trap’ where their remaining mortgages were more valuable than their properties, making it impossible to sell their houses to pay off their mortgage. Repossession rates significantly increased and for a while discredited the promise of the housing market as a place to make easy money.

The arrival of the Labour government in 1997 did introduce some changes to Right to Buy. They increased the length of tenancy that entitled Right to Buy, decreased the discount, especially in areas of reduced housing stock, and offered to buy back homes where owners were struggling with mortgage payments. They claimed they planned to increase house-building, but as the Housing Completion graph above (and repeated here) shows, there was some increase between 2000 and 2008, but not at all comparable to the building rates of the 1960s.

Why didn’t house building increase under Labour?

The impact of house prices on political ‘well-being’ was certainly experienced by both political parties. Incumbent governments took heed. The house price crash of the early 1970s, and the early 1990s both saw Conservative governments lose much support. Through the 1980s, some people wanted to blame the decline in Labour support on the increase in property ownership. Although council house sales had shown some volatility, the issue of ownership revolved much more about utility-share ownership. The Conservatives had sold shares in gas, electricity and water, and Labour promised to re-nationalise these industries which was probably unpopular with working-class owners of these new shares, despite the overall unpopularity of the privatisation programme.[28]

By the 2001 election, however, the ‘well-being’ effect of home-ownership was showing as new homeowners were slightly (8%) more likely than their renting counterparts to vote Labour rather than Conservative because the rising prices of the housing market was seen as a measure of the success of the government. [29]

It wasn’t so much that property-owning created support for a particular party, but the property market was experienced as barometer for the whole economy. This association had gone back a long time (some say even to the seventeenth century[30]), and indeed, the development of capitalism rested on the creation of a market in agricultural rent with the idea of ‘improvement’ of the land[31]. But the Labour Party of the late 1990s adopted this assumption and made it into their new founding credo.

Once the Labour Party had based its new success on developing a relationship with the growing middle classes, so they perceived that they could keep middle class support by ensuring rising property prices. And indeed they could, until the impact of the 2008 financial crash slowed house price rises for a few years (and increased repossessions, see graph again above). Part of their justification for making the Bank of England independent in 1997 was to claim that interest rates (and therefore mortgage rates) were politically independent of government. And this may have constrained their hand, but really it allowed the Labour Party to claim that rising house prices (and relative stability in mortgage interest rates) were a product of good wider policy, not through political tampering.[32] Although behind the scenes, there were many policy decisions that supported the housing bubble, above all stagnant completion rates so that housing supply remained restricted.

The increase in house prices is steepest and longest in the graph (below) through the years 1997 to 2008; the years Labour were in power until the financial crisis (and has climbed again subsequently).

(Data for graph from [33])

Expanding the housing bubble

One of the most significant encouragements to the development of the housing bubble was the mortgage lending that lay behind the rising prices. This had happened before. In the 1930s, the reduction in interest rates, just at a time when construction costs were falling and average wages were slightly increasing, enabled a housing boom between 1933 and 1935 fuelled by giving relatively cheap mortgages to an emerging middle class.[34] What had been previously provincial building societies and mutuals looked at expanding to become national institutions and competed with another for the newly liberalised mortgage market. [35] The ‘cheap money’ of the 1930s was funnelled into house building via the mortgage companies:

The reduction in interest rates during the early 1930s – following Britain’s departure from the Gold Standard and the government’s adoption of a cheap money policy – lowered minimum instalments, but was insufficient, in itself, to widen accessibility significantly. Of crucial importance was the action of the building societies. Following the onset of cheap money they were viewed as relatively high-interest, low-risk savings vehicles and experienced a heavy inflow of funds. They responded by trying to expand their lending, in a competitive process of undercutting each other on ‘easy terms’.[36]

The low initial deposits, sometimes as low as £5 (as a partial payment for £25), and repayments that were close to rental values due to low interest rates, meant that many people become property owners instead of tenants. Owner-occupation had gone from a mere 10% in 1914 to 32% of homes by 1938. In the same period, rental properties had decreased from 89% to 68% (the later figure includes 11% rented now from Local Authorities).[37] But what the graph below reveals is that local authority rentals never provided even 50% of the housing. The attractiveness of home-ownership was being able to leave the private rental market, especially when interest rates and initial deposits were low.

(Data for graph from [38])

The other side of those low interest rates and low deposits was the discovery of ‘cheap money’ for the government. Two reductions in interest rates in 1932 and 1933 boosted house construction and seemed to produce a sizable ‘feel-good’ factor. It had it limits, however. Another decrease in interest rates after 1935, did not further boost the market in mortgages as it was hard to lower mortgage rates sufficiently to further expand the numbers able to pay.[39]

The rise in mortgages had two impacts: first, it allowed a massive extension of credit into the UK economy as banks were permitted to lend with a much lower level of capital to back it up (increasingly virtually none, allowing the banks to print money).[40] Second, as increasing numbers of individuals had mortgages, so they perceived the success or failure of the UK economy in terms of rising house prices, rather than in terms of more or better jobs or even overall growth, which was always a distant phenomenon for most people. The housing bubble didn’t really burst in the 1940s because the Second World War stopped construction, paused many sales, and destroyed many old houses. But since the 1980s, the housing bubble has continued to grow.

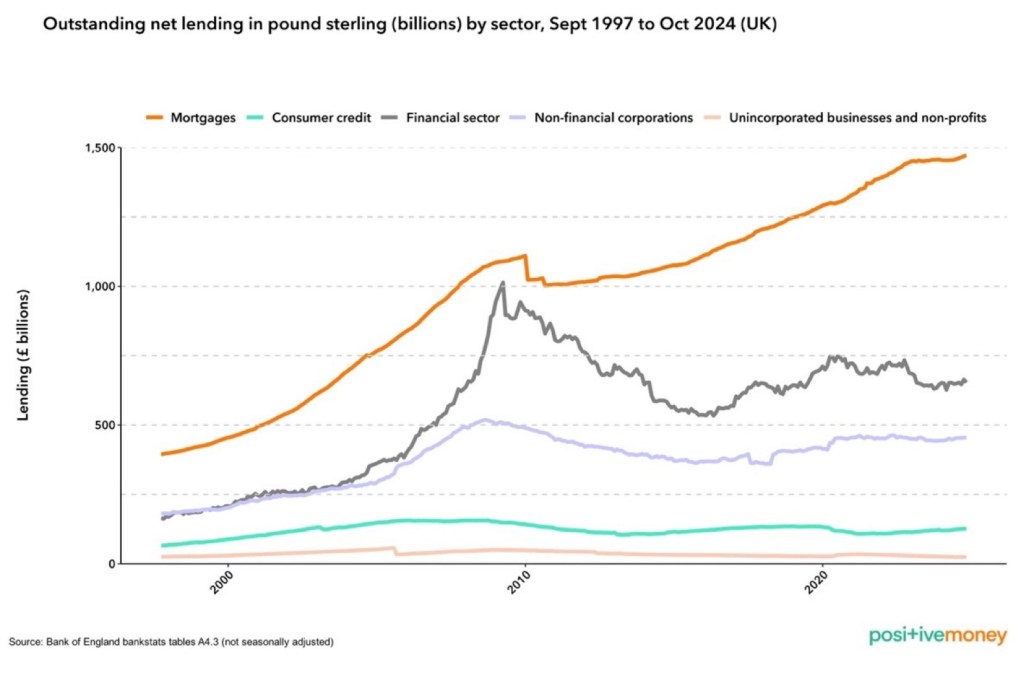

The 1980s, not only produced the Right to Buy, but also bank deregulation which allowed the banks to diversify into the mortgage sector with the same competitive advantages as the building societies. Between 1930 and 1937, the building societies’ lending had doubled in value and doubled in numbers they lent to.[41] Between 2000 and 2010, the amount of mortgage lending had more than doubled again. [42]

The graph below shows that mortgage lending has continued to rise, despite a hiccup with the financial crash of 2008.

The housing bubble since the late 1990s was not unique to the UK, although it was probably worse in the US and UK compared to other countries. Very low interest rates, the deregulation of the banks and the development of selling mortgages repackaged as junk bonds created a situation where the banks were effectively printing money with little restraint. When the 2008 crash happened, credit was expanded through Quantitative Easing to offset the crisis, although later some attempt was made to reduce financial credit. The overall value of mortgages have, however, continued to increase.

Unlike in the 1930s, the rise of lending by the mortgage industry has not led to a rise in house construction, only a rise in house prices. Investment in other activities, non-financial businesses and infrastructure projects, has also remained low. This was happening in the period 2000-2010, although there was some increase in non-financial corporate credit (although less than the finance sector), but subsequently, credit other than for mortgage loans has flatlined or even decreased. Unsurprisingly, along with increasing energy prices, this has encouraged inflation to rise too. As housing increased in price, so land also becomes more highly valued and as land prices have risen, so it has become harder to build infrastructure projects. For example, HS2 may turn out to be a doomed project, but part of the reason for spiralling costs was the cost of compulsory (and voluntary) land and house purchases.[44]

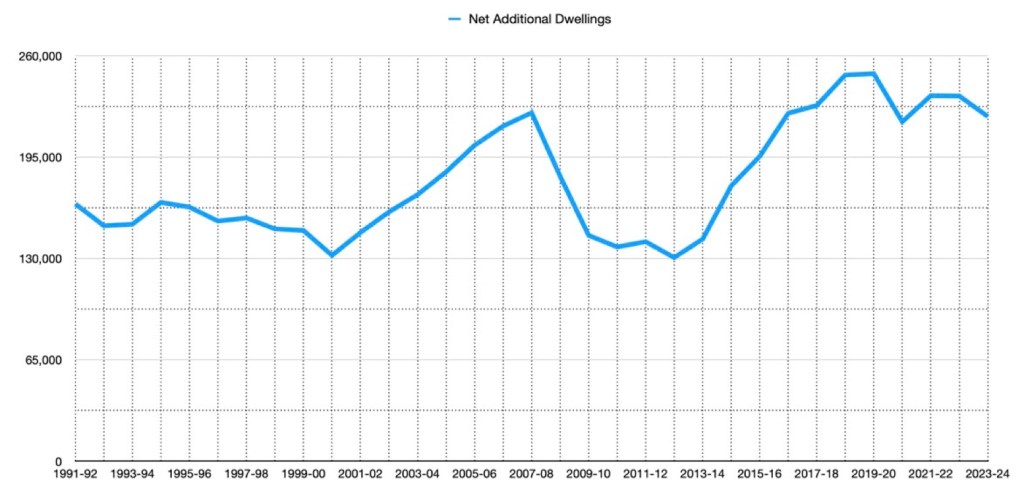

For the past 100 years, successive governments have promised to build more houses. Very few have succeeded, apart from Ramsay MacDonald (National Labour coalition) 1931-35, Winston Churchill (Conservative) 1951-55, and Harold Wilson (Labour) 1964-70. Tony Blair delivered on the low interest rates, but it only facilitated higher prices and an increase in overall mortgage credit. Despite an overwhelming majority in Parliament, the Right to Buy was never repealed under Labour. It is still the case that local authorities are only allowed to use (within three years) 30% of the receipts of sales for new housing (60% of sales goes to the Treasury, unless receipts from sales have paid off previous council debt). Some councils have become inventive and created not-for-profit companies to build and rent houses so as to avoid Right to Buy legislation, but social housing has expanded by a few hundred a year, not the few hundred thousand needed.[45] And though net dwelling growth has grown over the past 30 years, it hasn’t been significant compared to the population growth over the same period[46]:

(Data from [47] including new builds, conversions and demolitions)

Governments have talked of the need for house building, of the need to cut planning restrictions and the growing population’s demand for more housing, but they have failed to change legislation that would allow local authorities to build and keep their houses. They have also allowed the liberalisation of the mortgage market to continue to add fuel to the fire of rising prices so that everyone (homeowners being a majority of the population since 1970s) can feel good about the rising value of their flat or house and being able to pay off their mortgage on its sale. Fuelling the housing bubble has proved to be central to successive governments and so home ownership has affected politics: affecting government policy more clearly than the political identification of the home-owners. Councils’ planning decisions have also supported political divisions as social housing has been concentrated in unpopular areas, while reserving the ‘better’ areas for regeneration and gentrification. This enables councils to avoid middle class revolts which has the consequence of entrenching social divisions.[48]

One of the other ways we can see that government policy has contributed to low house building rates, despite the official commitment to house-building, is the lack of training for construction workers. To meet current targets, the Construction Industry Training Board (CITB) estimates that 250,000 new training and apprenticeships need to be found by 2028.[49] Much of the immigration in the period 2000-2010 supported the building industry for that decade, but coming from the EU, many of those people have returned to Europe,[50] encouraged by Brexit and lockdown and the drop in construction finance after 2008. Since Brexit, the massive increase of immigration has been from non-European countries[51] and more directed to the care industry[52]. Some construction methods have become more efficient, such as pre-fabricated brick panels and the tendency to reducing on-site complications. However, building has remained pretty labour-intensive and the loss of skilled workers does represent a real problem for the current government plans.[53] The fewer available construction industry workers has also tended to inflate the cost of house maintenance for home-owners.

The result is that home ownership has become much more expensive for people as they pay higher prices for their homes both initially and to maintain them in subsequent years. It is 150 years since house prices were as expensive as they are now relative to average earnings.[54] Housing, as a proportion of household expenditure is now over 20% (although these figures include fuel consumption too).[55] As a result, ownership is only seen as marginally better than renting because landlords are also charging high rents due to restricted supply. Standards in renting have also decreased as the Conservatives thought that by reducing onus on landlords would stimulate the housing market even further.

As a consequence, the question of housing affects almost everyone and its political significance has only grown while governments have become even more fearful of triggering a burst in the bubble. Home ownership has dropped from its high of 69% in 2005 to 64% of households, but that is still a very significant section of society.[56]

To some extent, the past two years of inflation have effectively reduced real asset values as the money is worth less. To repeat this graph:

(Data for graph from [33])

More monetary inflation has the result of reducing the value of assets such as housing. And it may well continue but the inflation is also politically unpopular. The alternative is a serious recession which will reduce prices. But house prices need to decrease relative to other prices to stop being such a large proportion of household expenditure, and this seems also to be the one thing that every government seeks to avoid.

For a hundred years, every government has talked of the need to build more houses. Very few have managed it and increasingly less so as the risk to the housing bubble has also increased. [57] Printing money through expanding mortgages is an executive drug to which government is addicted. It no longer stimulates growth or building, but its removal is almost unthinkable. Meanwhile, home ownership appears to the population as a way to avoid unscrupulous landlords and pay ‘rent’ into one’s own mortgage rather than to someone else’s. Ownership appears as a small measure of freedom in what has appeared to be a fairly stable marketplace, but one that may not last. Behind Thatcher’s concern to create a ‘property-owning democracy’ was her thought that: ‘every family should have a stake in society and the privilege of a family home should not be restricted to the few’. [58] As it happens, a majority of the population already owned their homes by the 1980s, not so much thanks to Conservative Right to Buy policy, but more because of the expansion of building and low mortgages since the 1930s. Although home ownership is lower than its peak, it still constitutes the majority of tenure and so when the housing bubble bursts, most of the population will be affected.

Footnotes:

[1] Aled Davies, ‘“Right to Buy”: The Development of a Conservative Housing Policy, 1945–1980’, Contemporary British History 27, no. 4 (2013): 424, https://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2013.824660.

[2] ‘Live Tables on Dwelling Stock (Including Vacants)’, GOV.UK, 5 December 2024, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-dwelling-stock-including-vacants.

[3] Michael Ball, Housing Policy and Economic Power : The Political Economy of Owner Occupation (London ; New York: Methuen, 1983), 283.

[4] Friedrich Engels, The Housing Question, 2nd ed. (orig 1872) (London: Union Books, 2012), https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1872/housing-question/index.htm.

[5] Clive Turner and Richard Partington, ‘Homes Through the Decades: The Making of Modern Housing’ (Milton Keynes: NHBC Foundation, March 2015), 40, https://www.nhbc.co.uk/binaries/content/assets/nhbc/foundation/homes-through-the-decades.pdf.

[6] Sonya O. Rose, Which People’s War?: National Identity and Citizenship in Wartime Britain 1939-1945, Illustrated edition (Oxford ; New York: OUP Oxford, 2003).

[7] Lord Llewellin, ‘The Housing Situation – Hansard – UK Parliament’ (House of Commons, 21 June 1950), https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/1950-06-21/debates/6ba14fba-68c1-4169-982e-1a81c62b585e/TheHousingSituation.

[8] Lieut-Colonel Elliot, ‘Hansard – UK Parliament’ (House of Commons, 13 March 1950), https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/1950-03-13/debates/c97415d3-6c43-4dca-8d3f-fda900f18625/Housing.

[9] Harriet Jones, ‘“This Is Magnificent!”: 300,000 Houses a Year and the Tory Revival after 1945’, Contemporary British History 14, no. 1 (2000): 109, https://doi.org/10.1080/13619460008581574.

[10] Rowan Moore, ‘From Right to Buy to Housing Crisis: How Home Ownership Killed Britain’s Property Dream’, The Guardian, 29 October 2023, sec. Society, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/oct/29/right-to-buy-housing-crisis-home-ownership-britain-property-rowan-moore.

[11] Turner and Partington, ‘Homes through the Decades’, 21.

[12] Turner and Partington, 22.

[13] Turner and Partington, 19.

[14] Davies, ‘“Right to Buy”’, 429.

[17] Ian Mcallister and Donley T. Studlar, ‘Popular versus Elite Views of Privatization: The Case of Britain’, Journal of Public Policy 9, no. 2 (1989): 163, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00008102.

[18] Mcallister and Studlar, ‘Popular versus Elite Views of Privatization’.

[19] Simon James, Bill Jordan, and Helen Kay, ‘Poor People, Council Housing and the Right to Buy’, Journal of Social Policy 20, no. 1 (1991): 34, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279400018468.

[20] James, Jordan, and Kay, 30.

[21] Avner Offer, ‘British Manual Workers: From Producers to Consumers, c. 1950–2000’, Contemporary British History 22, no. 4 (2008): 10, https://doi.org/10.1080/13619460802439408.

[22] Brian Milligan, ‘Right-to-Buy: Margaret Thatcher’s Controversial Gift’, BBC News, 9 April 2013, sec. Business, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-22077190.

[23] Wendy Wilkins, ‘The Right to Buy (House of Commons Research Paper)’, House of Commons Research Paper, House of Commons Library (London: House of Commons, 30 March 1999), 13, https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/RP99-36/RP99-36.pdf.

[25] Andy Beckett, Promised You A Miracle: Why 1980-82 Made Modern Britain (London, UK: Allen Lane, 2015).

[26] Milligan, ‘Right-to-Buy’.

[27] Tejvan Pettinger, ‘UK Housing Market Stats and Graphs | Economics Help’, accessed 21 February 2015, http://www.economicshelp.org/blog/5709/housing/housing-market-stats-and-graphs/.

[28] Peter Saunders, ‘Privatization, Share Ownership and Voting’, British Journal of Political Science 25, no. 1 (1995): 137, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400007092.

[29] Mark Huberty, ‘Testing the Ownership Society: Ownership and Voting in Britain’, Electoral Studies 30, no. 4 (2011): 789, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2011.07.006.

[30] Laura Brace, The Idea of Property in Seventeenth-Century England: Tithes and the Individual, (Manchester, UK ; New York : New York: Manchester University Press ; Distributed exclusively in the USA by St. Martin’s Press, 1998).

[31] Ellen Meiksins Wood, The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View, Reprint edition (London New York: Verso, 2017).

[32] ‘25 Years of Bank of England Independence Shows We Need a New Approach – Positive Money’, Positive Money, 6 May 2022, https://positivemoney.org/archive/25-years-of-bank-of-england-independence-shows-we-need-a-new-approach/.

[33] House Price Crash, ‘Nationwide UK House Prices Index Adjusted for Inflation [’Real’ Prices]’, HousePriceCrash, accessed 8 December 2024, https://www.housepricecrash.co.uk/indices-nationwide-national-inflation/.

[34] R. M. MacIntosh, ‘A Note on Cheap Money and The British Housing Boom, 1932-37’, The Economic Journal (London) 61, no. 241 (1951): 167–73, https://doi.org/10.2307/2226630.

[35] Peter Scott and Lucy Ann Newton, ‘Advertising, Promotion, and the Rise of a National Building Society Movement in Interwar Britain’, Business History 54, no. 3 (2012): 400, https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2011.638489.

[36] Peter Scott, ‘Marketing Mass Home Ownership and the Creation of the Modern Working-Class Consumer in Inter-War Britain’, Business History 50, no. 1 (2008): 7, https://doi.org/10.1080/00076790701785581.

[37] Turner and Partington, ‘Homes through the Decades’, 40.

[38] Turner and Partington, 27.

[39] MacIntosh, ‘A Note on Cheap Money and The British Housing Boom, 1932-37’, 173.

[40] Positive Money, ‘The Proof That Banks Create Money’, PositiveMoney, 3 April 2013, https://positivemoney.org/archive/proof-that-banks-create-money/.

[41] Scott and Newton, ‘Advertising, Promotion, and the Rise of a National Building Society Movement in Interwar Britain’, 405.

[42] Alec Haglund, ‘How Is Bank Lending Shaping the UK Economy?’, PositiveMoney, 4 December 2024, https://positivemoney.org/update/how-is-bank-lending-shaping-uk-economy/.

[44] Helen Pidd and Helen Pidd North of England editor, ‘£600m of Public Money Spent Buying up Property in North of England for HS2’, The Guardian, 29 September 2023, sec. UK news, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/sep/29/600m-of-public-money-spent-buying-up-property-in-north-of-england-for-hs2.

[45] Oliver Wainwright, ‘Meet the Councils Quietly Building a Housing Revolution’, The Guardian, 28 October 2019, sec. Cities, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/oct/28/meet-the-councils-quietly-building-a-housing-revolution.

[46] Office for National Statistics, ‘Overview of the UK Population – Jan 2021’, Office for National Statistics, 14 January 2021, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/overviewoftheukpopulation/january2021.

[47] Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, ‘Housing Supply: Net Additional Dwellings, England: 2023 to 2024’, GOV.UK, 28 November 2024, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/housing-supply-net-additional-dwellings-england-2023-to-2024/housing-supply-net-additional-dwellings-england-2023-to-2024.

[48] Colin Wiles, ‘In Cities Where House Prices Are High, Right to Buy 2 Is Nothing Less than Social Cleansing | CityMetric’, City Metric, 29 May 2015, http://www.citymetric.com/politics/cities-where-house-prices-are-high-right-buy-2-nothing-less-social-cleansing-1086.

[49] CITB, ‘Over 250,000 Extra Construction Workers Required by 2028 to Meet Demand – CITB’, 15 May 2024, https://www.citb.co.uk/about-citb/news-events-and-blogs/over-250-000-extra-construction-workers-required-by-2028-to-meet-demand/.

[50] Office for National Statistics, ‘Overview of the UK Population – Jan 2021’.

[51] ‘Countries of Birth for Non-UK Born Population’, Trust for London, 2022, https://trustforlondon.org.uk/data/country-of-birth-population/.

[52] Madeleine Sumption and Ben Brindle, ‘Work Visas and Migrant Workers in the UK’, Migration Observatory, 30 August 2024, https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/work-visas-and-migrant-workers-in-the-uk/.

[53] Michael Race, ‘UK “doesn’t Have Enough Builders” for Labour’s 1.5m Homes’, BBC News, 14 December 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c5yg1471rwpo.

[54] Duncan Lamont, ‘What 175 Years of Data Tell Us about House Price Affordability in the UK’, Schroders Perspective, 20 February 2023, https://www.schroders.com/en-gb/uk/intermediary/insights/what-174-years-of-data-tell-us-about-house-price-affordability-in-the-uk/.

[55] Costa OECD Affordable Housing Database, ‘Household Related Expenditure of Households’, no. Indicator HC1.1 (15 April 2024), https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/data/datasets/affordable-housing-database/hc1-1-housing-related-expenditure-of-households.pdf.

[56] ‘Live Tables on Dwelling Stock (Including Vacants)’, GOV.UK, 5 December 2024, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-dwelling-stock-including-vacants.

[57] Wendy Wilson, ‘Stimulating Housing Supply – Government Initiatives – Commons Library Standard Note’, UK Parliament, 9 December 2014, http://www.parliament.uk/briefing-papers/SN06416/stimulating-housing-supply-government-initiatives.

[58] Brian Lund, ‘A “Property‐Owning Democracy” or “Generation Rent”?’, The Political Quarterly 84, no. 1 (2013): 56.